After carefully making our precarious 5 mile exit from Nutallburg, the next stop on our West Virginia ghost town tour was Thurmond – aka the place that seemed like the easiest to find out of the multitude of dubiously mapped options.

Unlike Nutallburg, Thurmond was bustling epicenter of train travel and commerce, seeing more transportation of coal, rather than the manufacturing of it. Formally incorporated in 1900, the town was named for Confederate Captain William Thurmond, who was offered 73 acres of land along the river as a good will gesture for just $20. The C&O railroad was routed through the area shortly after, but the town was slow to grow with only one house constructed at the time. It was not until Thomas G. McKell of neighboring Glen Jean negotiated with the railroad for a branch up Dunloup Creek, that Thurmond became the boom town it was known to be, with the line becoming one of the railroad’s busiest branches. Despite this growth of business for both parties, McKell and Thurmond became bitter enemies.

Like Nutallburg, and the most of the area’s ghost towns, Thurmond is accessible via a long, winding, narrow road – but this one is paved almost the entire way, so it at least feels like you’re supposed to drive a car on it. To get to Thurmond, you have to start out in the aforementioned Glen Jean, which was actually the bigger of the two towns at the time – Thurmond was viewed like its suburb. Unlike McKell, Captain Thurmond was a staunch Baptist with a distaste for drinking and gambling, thus imposing a town-wide ban on both. His prosperous neighbor, however, decided to take advantage of this, first, by taking over the western bank of Thurmond and reclassifying it as a Glen Jean, despite it being 7 miles away (I love how that was even a thing that was possible), and then promptly building the imposing, and now legendary, DunGlen Hotel to host a feast of vice, including dancing, drinking, gambling and prostitution. (Fun fact: the Dunglen was said to host the longest lasting poker game in history, lasting 14 years! The only reason why the game stopped was because the hotel burned down.) The hotel quickly thrived and thus began the lifelong hatred between McKell and Thurmond.

The Dunglen, as it would have been seen across the river from the seething eyes of Captain Thurmond.

When reading accounts of past visitors, one gentleman recalled stepping over a dead body when he first got off the train in Thurmond. There were also many stories of frequent shoot outs, usually from poker games gone awry. There was also a saying from locals that lasted decades, “The only difference between Hell and Thurmond is that a river runs through Thurmond.” Despite the feuds and the sketchy reputation, Thurmond still prospered. Fifteen passenger trains passed through town a day – its depot serving as many as 95,000 passengers a year. The town’s stores and saloons did remarkable business, and its hotels and boarding houses were constantly overflowing. However, this prosperity was brief. As the automobile was becoming more popular, the highway took more and more business away; and with the advent of diesel locomotives, and less coal coming in from local mines, the town began a steady decline.

The local vice began to curtail, as well, with the passing of Prohibition in 1914, effectively ending McKell’s prized red light district. In 1922, a large fire destroyed parts of Thurmond, and finally the DunGlen Hotel was set ablaze in 1930. Shortly after, the rest of the town was a slowly collapsing house of cards until the town became a virtual ghost town (save for a handful of residents) by the 1950s.

When finally reaching Thurmond after miles of narrow road, we entered the town via a tight two-lane bridge, with one narrow lane for cars and the other for train travel, which I was grateful to not have to share with an locomotive. To our surprise, there were a few workers out and about doing some sort of work on the tracks. It was unclear where we were allowed to park, or if we were even supposed to be there, so we kept driving along the road next to the tracks.

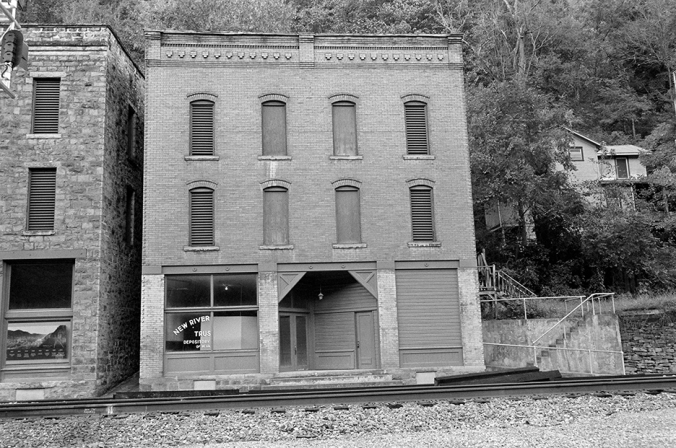

The town has a few of its commercial buildings and train station still standing next to the tracks, looking like an old western town straight out the movies…but in the South. There are also several residential buildings still in tact, precariously hanging on the hillside behind the tracks. As we continued to drive, surveying the buildings around us, our paved road turned to gravel, and the only stopping point seemed to be when our car got stuck. With no where to turn around, we had to back up for a fairly long stretch of curved road, hoping that the construction workers wouldn’t notice our idiocy (or get hit) – but for the duration of our visit, I never saw them so much as glance at us.

Like the rest of the New River Gorge ghost towns, the town is property of National Park Service. The train station was turned into an information center, but was closed at the time of our visit, and some of the commercial buildings housed a display in their windows of some old photos of the town. The tracks, however, are still active, with a few trains passing through daily. Thurmond is also still trafficked by Amtrak. While it is not a regular stop (it was discontinued as a stop in 2006), trains will stop there if someone is on the platform or if a passenger on the train requests the stop. To date, Thurmond is the 2nd least used station, just after Sanderson, Texas.

With not much poking around to do along the tracks, we proceeded up the hill to see what was left of the houses behind us. Most of the houses were cleaned out with nothing left inside aside from peeling paint and rotting wood. Sadly, no signs of gambling or prostitution. We did come across one questionable barn that looked like something large and menacing broke its way out of. We also ran across a lone chicken that somehow found its way to Thurmond. Maybe he’s connected to the barn?

Despite the seeming desolation, Thurmond is not quite a ghost town just yet. According to a 2013 census, the population is holding steady at a stubborn 5 people. Where they were located, I’m not entirely sure, since we did poke through most of the houses, but perhaps that better explains our chicken friend’s existence.

Pingback: West Virginia Ghost Towns (Part 1): Nuttallburg | Minsky's Abandoned America

I was sent here by Auralnaut Zack but stayed because of the writing that gave me the impression of what it’d be like to there as well as the nuanced history. 🙂

LikeLike

I’m glad you enjoyed it! Zak also has a tendency to pop up in these posts and photos from time to time, too. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you’re enjoying it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Glen Jean School | Minsky's Abandoned

Have you seen the movie Matewan? It was filmed in Thurmond> I sugest you take a look. Worth a look and you’ll probably feel nostalgic for Thurmond.

LikeLike

I haven’t seen it – I will definitely check it out. Thank you!

LikeLike

i have family members that payed small roles in that movie. i cant remember all ,but i do recall my grandmother being in it. my dad and his side of the family are originally from Thurmond.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My granddad and my dad both were born in Thurmond. my granddad use to have a bar in Thurmond called the ” river rat inn ” , he had to close the business in 1987 due to the National Park service forced him to do so when they took over Thurmond. i have many good memories there when i was a kid growing up. my granddad passed away in 1998,i sure do miss him alot and i miss the days being a kid when he had his bar in Thurmond. ( R.I.P. Rudy Humphery )

LikeLiked by 1 person